Ruby on Rails continues to be an extremely powerful yet developer-friendly solution for tackling all manner of web projects, and this trend doesn’t appear to be abating anytime soon. Due to Rails’ insistence of “convention over configuration“, however, it can often be difficult to precisely determine how you should go about solving a particular problem or what the Ruby on Rails best practices might actually be as the technology rapidly changes from year to year and from version to version.

While Rails is far too massive a topic to cover everything, in this article we’ve assembled some of the most fundamental Ruby on Rails Examples for 2022 as you embark on your own development journey with Rails and the amazing possibilities with which that entails.

Ruby on Rails Examples: What You Need to Know

1. Jump Start with Scaffolding

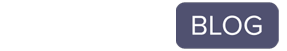

Scaffolding is a great feature of Rails for individuals new to the development, or perhaps those just new to Rails itself. Scaffolding is one of the many generate commands that allows you to automatically create all the framework files you need for a simple object, including the model, controller, database migration file, and basic views.

For example, if you want to create a simple Book model and all associated components, you might run the following command in the terminal.

![]()

Here we’re asking rails to generate a scaffold object called Book and then specifying the model fields afterward in the format of field_name:data_type.

You should immediately see an output with all the generates files and paths.

Believe it or not, you now technically have a working rails application! You can run your rails server ($ rails s) and browse to your localhost to see your functional page. It won’t be pretty, but as is the beauty of Rails, it should just work out of the box with the fields behaving as you expect.

While scaffolding is a great jumping-off point for developers still learning Rails, much of the code generated by the scaffold command will be wasted or not appropriate for most projects, so be weary of all the files and code created when running this command in your own projects.

2. Properly Associating Many to Many

During development, you may find you need to associate two models through a many-to-many relationship, whereby each instance of a model can be matched with any number of instances of the other model, and vice versa.

There are essentially two methods by which to create such an association, so we’ll briefly discuss both options and why one method in particular (has_many :through) is the far superior implementation.

-

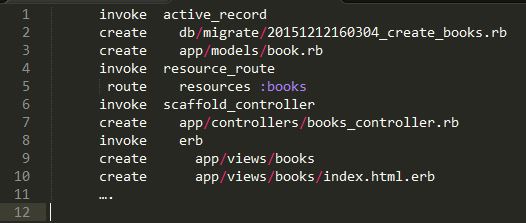

The has_and_belongs_to_many Association

For a truly basic many-to-many relationship of two models, you can declare a has_and_belongs_to_many association in both models, like so:

This would then require you to create a simple database table to represent that relationship. Your migration file would look something like this:

Now, in addition to the separate authors and books tables, you also have the authors_books table that simply has two columns to associate the id field of one author and one book. An instance of a model can then reference the other through this association:

-

Why the has_many: through Association Wins

While has_and_belongs_to_many is sufficient for the most rudimentary many-to-many relationship, it’s a very weak and limited solution, particularly for future-proofing.

The biggest limitation with the has_and_belongs_to_many association is that the associative model it creates — authors_books in our example above — has no room for expansion in the future. Later in development, imagine we need a model field that indicates which chapter(s) of a book a particular author worked on.

With has_and_belongs_to_many, there’s no simple way to track that information, because neither the books nor authors database table would allow for storage of all the necessary information (the book plus the author plus the chapters). Suddenly, the has_and_belongs_to_many association we’re using needs to be scrapped or a huge workaround needs to be figured out so we don’t screw up live data.

Enter the far superior solution of the has_many :through association. This model configuration utilizes not only a third database table but most importantly, also utilizes a third model through which the two base models can be associated with one another. With access to the third “connector” model, we now have the freedom to add attribute fields or any other logic we might need in the future.

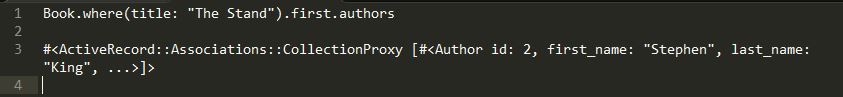

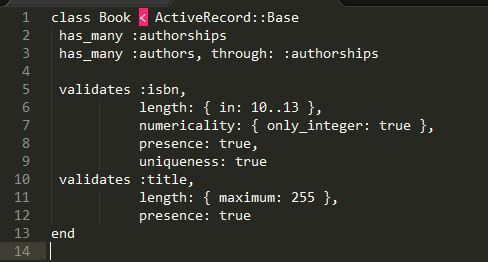

To use the has_many :through association for our example, we’d do something like this:

With the authorship model in place for our many-to-many relationship between books and authors, we can now easily modify the authorship model in the future, adding a column for :edited_chapters or anything else we might need.

In short, while it requires a bit more time and effort to initially setup, you should always use the has_many :through association anytime a many-to-many relationship is required.

3. Generating Initial Database Data

While most data during development can be generated on the fly during your testing procedures, you may often find yourself in a situation where you need specific dummy data to fill up your database while you work and tweak your code or even data for the live environment. Luckily, the db/seeds.rb file exists exactly for this purpose.

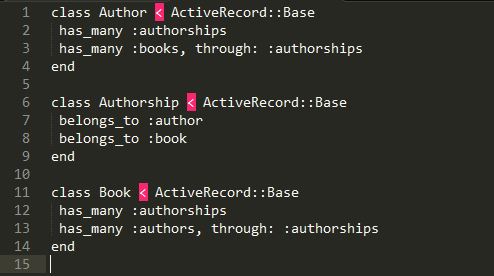

Since seeds.rb is of course a Ruby file, it can contain almost any Ruby code you need in order to create your initial data. For example, our books project might add a couple books and authors like so:

Once you have some code in seeds.rb to generate data, you can populate your database from the terminal:

![]()

There are even great Ruby gems like the Faker gem for creating more realistic dummy data such as names, colors, and URLs.

4. Utilize Active Record Validations

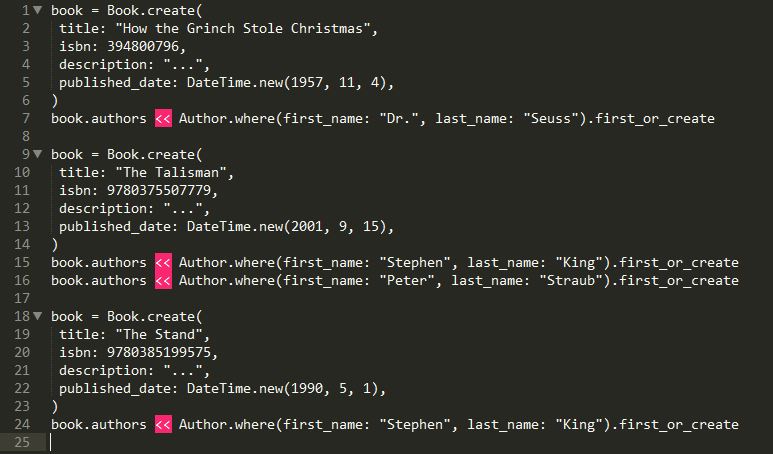

All applications — particularly web applications that accept user data — need a solid foundation of data validation, and directly within the model is a great place to perform these initial validations. Proper validation will ensure that only valid data is processed and ultimately saved to your database.

Rails offers plenty of built-in validation helpers, or you can even create your own custom validation, so there’s no excuse not to validate your data as accurately as possible before saving it to the database.

As a simple example, here we’re validating that our book title exists and is no larger than 255 characters. We’re also validating that the ISBN is a unique integer between 10 and 13 characters.

5. Robust Models and Tiny Controllers

It is typically the best practice in Rails to keep the majority of your business logic and execution within your models, and thus away from your controllers. That isn’t to say the paradigm of developing “fat models” is necessarily appropriate in all cases, and of course, your design pattern should be based on the needs of the project.

Yet, at the very least, the concept of tiny controllers (and by extension, fewer objects passed to your views) is a good practice to get into. To achieve this, you need look no further than using a facade pattern, which effectively provides a higher-level interface that can aggregate important functionality and pass that interface along to lesser interfaces.

In the case of Rails, this means creating a facade class that exposes a variety of methods and objects needed in a particular view, without requiring the controller to directly access all of these methods and objects individually.

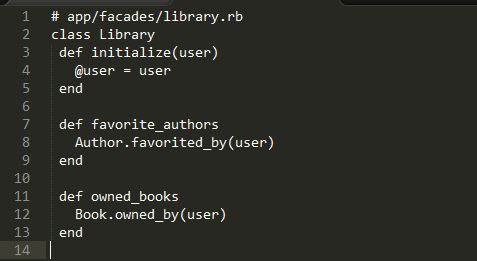

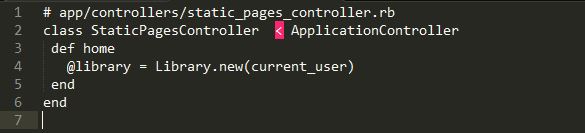

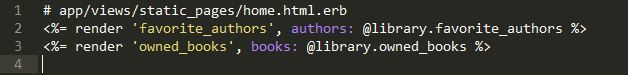

Here’s a simple example of using a facade in our Book Dojo application:

A basic example, but here we have the Library class with acts as a facade to gather information about the current user along with his or her favorite authors and owned books.

We can then simply pass that information along to the controller that will make use of it with only one single instance object, @library.

Now, the view of the home page that renders this also needs only to receive one instance object of @library, and can invoke the methods therein to get the appropriate information.

While this is a simple example, it should give you an idea of how a facade pattern can clean up your controllers and views considerably.

6. Properly Managing Dates, Times, and Timezones

While Rails offers a number of useful classes and methods for manipulation of dates and times, it is not uncommon for developers to run into inconsistencies and issues when timezones begin to enter into the mix. Even for applications developed without a requirement of timezone support, often an application is actually dealing with a multitude of possible timezones.

Your Rails application will often need to correctly account for the timezone of the server running rails, the database server, and the Rails application itself.

To deal with these potential pitfalls, there are a few simple practices that you should begin implementing in your own development.

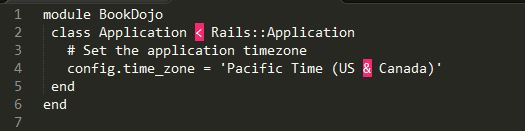

- Application Timezone

Begin by setting the timezone of your application, which can be done in the config/application.rb file using the config.time_zone method.

To see a list of appropriate timezone names, use the rake time:zones:all command in the terminal.

![]()

- ActiveRecord & UTC Conversion

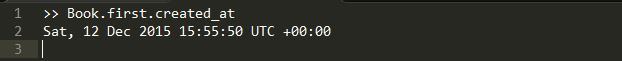

Rails stores all dates and times in the database in UTC. With config.time_zone set for your application, Rails will attempt to convert ActiveRecord attributes from the UTC stored in the database to your application timezone. This means if you retrieve a time attribute from an ActiveRecord instance, the timezone will be automatically converted to the application timezone before being output:

![]()

If config.time_zone is unspecified, you’ll get the actual stored database value, which is in UTC:

-

Use the Time Class, Not Date

If at all possible, always try to utilize the Time class in Rails instead of Date. This is simply because Date doesn’t innately manage time information, whereas the Time class does so, as expected.

-

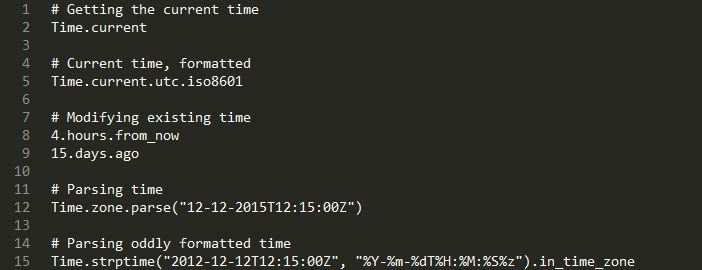

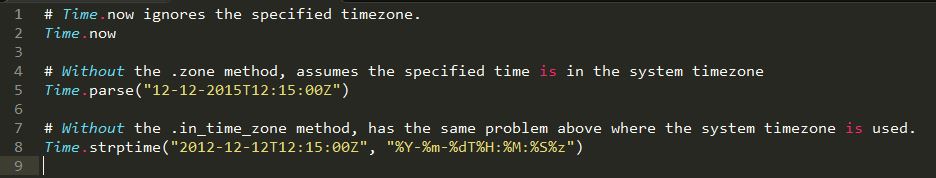

Parsing Input Times

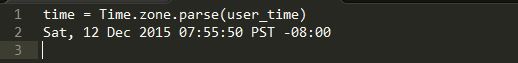

When you need to parse a date and time from another source, always use Time.zone.parse (instead of Time.parse) to make use of the timezone specified in your application’s configuration.

![]()

-

Beware of Database Engine and Time Comparisons

Be particularly mindful when performing comparisons of times from two different sources, since the comparison you expect may not actually be taking place.

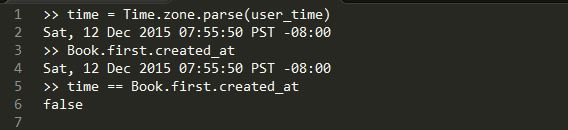

For example, imagine a real-world scenario where your application needs to compare a date and time stored in the database with a date and time specified by the user. The user will, of course, use a datepicker object and provide your application with a date and time with precision up to the second if you require it. The user input that is processed by your application might look something like this:

![]()

In the application code, you might parse that user-input time like so:

Now, if your application attempts to compare the time parsed from the user above with the same date and time from a record in the database, you will often find that the two times do not, in fact, match as you would expect, in spite of being identical down to the second.

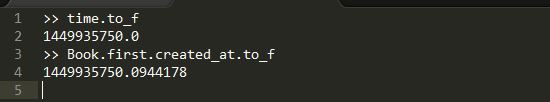

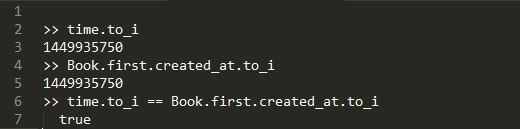

The issue here is that the database (in this case SQLite) may actually store time values with microsecond precision, whereas the user-specified time of course only has precision to the second. This difference can be seen by converting the times to floating point numbers:

To resolve this issue, be sure to convert your times to the appropriate precision first before making any comparisons. In the above example, if we only need to compare to the second, then the simplest option is to convert both times to integers, which is effectively evaluating the number of seconds in total:

On the flipside, also be aware of your database engine and what kind of time precision it is storing by default. This is particularly crucial for MySQL, which as of version 5.6.4 has support for times with fractional seconds, but you must configure your database to do so. See here.

Date and Time Cheat Sheet

To recap, here are a few good and bad practices working with time in Rails.

-

The Good

-

The Bad

Looking for more Ruby on Rails examples?

Ruby on Rails at Coding Dojo

Any of Coding Dojo’s four software development bootcamps can help you learn more about implementing Ruby on Rails? Which coding bootcamp is right for you?